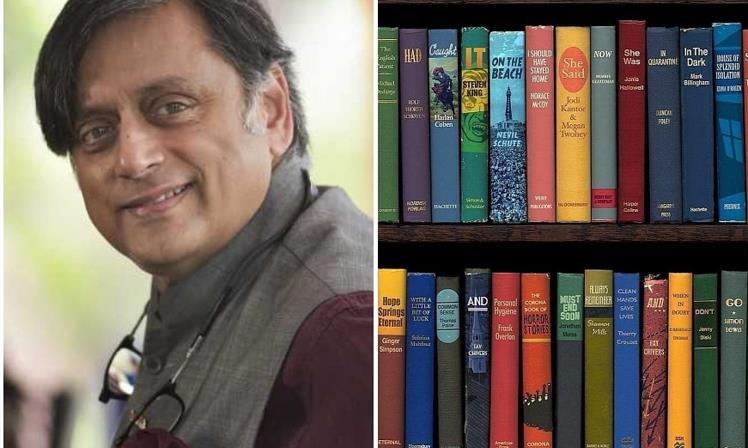

'We're All Minorities in India': Shashi Tharoor On Nationalism And The Constant Battle of Belonging

03-November-2020

There is a very defined trajectory to Shashi Tharoor's literary pursuits. Be it books like India: Midnight to Millennium (1997) and India Shastra: Reflections on the Nation in our Time (2015) or more recently, Why I Am A Hindu (2018) the politician and writer cannot move away from the themes of nationalism, secularism, and patriotism. In his latest offering titled The Battle of Belonging, Tharoor harks back to similar questions yet again and examines how our gendered, caste, and religious identities align with the rapidly evolving definition of nationalism, and patriotism.

The author says that despite the 'myriad problems' that India has, it is the democracy that has given Indian citizens of various caste, creed, culture, and cause the chance to break free of their age-old subsistence-level existence. The author writes, "There is social oppression and caste tyranny, particularly in rural India, but democracy offers the victims a means of escape, and often�thanks to the determination with which the poor and oppressed exercise their franchise�of triumph. The various schemes established by successive governments from Independence onwards for the betterment of the rural poor are a result of this connection between India�s citizens and the state."

"And yet, in the more than seven decades since we became free, democracy has failed to unify us as a people or create an undivided political community. Instead, we have become more conscious than ever of what divides us: religion, region, caste, language, ethnicity. The political system has become looser and more fragmented. Politicians mobilize support along ever-narrower lines of political identity. It has become more important to be a �backward caste�, a �tribal�, or a religious chauvinist, than to be an Indian; and to some it is more important to be a �proud� Hindu than to be an Indian," writes Tharoor in the book.

Tharoor points out that despite the illusion that some might possess that they are part of the 'majoritarian community' and therefore immune to the perils of the minorities, it is not true.

Tharoor writes:

"For, as I have often argued, we are all minorities in India. A typical Indian stepping off a train, say, a Hindi-speaking Hindu male from the Gangetic plain state of Uttar Pradesh (UP), might cherish the illusion that he represents the �majority community�, to use an expression much favoured by the less industrious of our journalists. But he, literally, does not. As a Hindi-speaking Hindu he belongs to the faith adhered to by some 80 per cent of the population, but a majority of the country does not speak Hindi; a majority does not hail from Uttar Pradesh; and if he were visiting, say, Kerala, he would discover that a majority there is not even male. Even more tellingly, our archetypal UP Hindi-speaking Hindu has only to mingle with the polyglot, multihued crowds thronging any of India�s major railway stations to realize how much of a minority he really is. Even his Hinduism is no guarantee of majority-hood, because his caste automatically places him in a minority as well: if he is a Brahmin, 90 percent of his fellow Indians are not; if he is a Yadav, a �backward class�, 85 percent of Indians are not, and so on. Or take language. As I have stated earlier, the Constitution of India recognizes twenty-two today�our rupee notes proclaim their value in fifteen languages�but, in fact, there are twenty-three major Indian languages (if you include English), and thirty-five which are spoken by more than a million people (and these are languages, with their own scripts, grammatical structures, and cultural assumptions, not just dialects�if we were to count dialects, there are more than

20,000).

Each of the native speakers of these languages is in a linguistic minority, for none enjoys majority status in India. Thanks in part to the popularity of Bombay�s Hindi cinema, Hindi is understood, if not always well spoken, by about half the population of India, but it is in no sense the language of the majority; indeed, its locutions, gender rules, and script are unfamiliar to most Indians in the South or Northeast. Ethnicity further complicates the notion of a majority community. Most of the time, an Indian�s name immediately reveals where he is from, and what his mother tongue is; when we introduce ourselves, we are advertising our origins. Despite some intermarriage at the elite levels in the cities, Indians still largely remain endogamous, and a Bengali is easily distinguished from a Punjabi. The difference this reflects is often more apparent than the elements of commonality. A Karnataka Brahmin shares his Hindu faith with a Bihari Kurmi, but feels little identity with him in respect of appearance, dress, customs, tastes, language, or political objectives. At the same time, a Tamil Hindu would feel that he has far more in common with a Tamil Christian or Muslim than with, say, a Haryanvi Jat with whom he formally shares a religion.

Why do I harp on these differences? Only to make the point that Indian nationalism is a rare animal indeed. This land imposes no narrow conformities on its citizens: you can be many things and one thing. You can be a good Muslim, a good Keralite, and a good Indian all at once."

Tharoor says that the basis of Indian nationhood is unusual in today�s world and while it works in practice, it doesn't hold very good in theory because it isn't tied to any particular language, or geography, or faith. The author writes,

"...Indian nationalism is the nationalism of an idea, the idea of what I have dubbed an ever-ever land�emerging from an ancient civilization, united by a shared history, sustained by pluralist democracy under the rule of law. As I never tire of pointing out, the fundamental DNA of India, then, is of one land embracing many. It is the idea that a nation may incorporate differences of caste, creed, colour, culture, cuisine, conviction, consonant, costume, and custom, and still rally around a democratic consensus. That consensus is around the simple principle that in a democracy under the rule of law, you don�t really need to agree all the time�except on the ground rules of how you will disagree.

The reason India has survived all the stresses and strains that have beset it for over seventy years, and that led so many to predict its imminent disintegration, is that it maintained consensus on how to manage without consensus. Today, some in positions of power in India seem to be questioning those ground rules, and that sadly is why it is all the more essential to reaffirm them now. What knits this entire concept of Indian nationhood together is, of course, the rule of law, enshrined in our Constitution."

The following excerpts from the book, The Battle of Belonging, have been published with permission from Aleph Book Company.

Leave a comment: (Your email will not be published)